Imagine a scenario in which a person graduates from three years of law school at the top of their class, passes the bar, and then has to take a full-time unpaid position for two years in order to be competitive for a job at a law firm, which only a tiny fraction of their fellow graduates will ever manage to land. Then imagine that after years of trying unsuccessfully to get one of those jobs, this lawyer finally gives up and decides to go out on their own—to hang up a proverbial shingle—only to discover that no one in their community is willing to pay for legal services.

This is the position that the vast majority of artists, arts workers, arts writers, curators, museum studies majors, and arts educators find themselves in, which is why many rely on grant funding—wondering every year if they will receive enough to be able to pay their bills and keep themselves alive.

Imagine if we expected this of dentists or electricians, therapists or architects? Imagine if, for example, the only way for commercial pilots to keep themselves afloat was to apply for grants from the Federal Aviation Administration, and that, in the years when none came through, they would need to get a job washing dishes at a restaurant at night so that they could still fly planes for free (or for minimum wage) during the day.

The reason these hypotheticals sound ridiculous is because we value these jobs and the people who do them. The reason that we accept the same circumstances as a reality for arts workers is because we1 see them as having tertiary value (at best), and as being largely uneducated, unskilled, or unnecessary. So, we should probably look at each one of these things individually.2

In fact, many artists, arts workers, and arts educators have terminal degrees in their fields—just like doctors, lawyers, and architects do. They study for years, accruing obscene amounts of debt to acquire MFAs and Ph.Ds, only to be told that their options are either to take a job with an unlivable wage3 or to get a better-paying job outside of their field.

A terminal degree isn’t a prerequisite for all arts workers (though it’s expected more often than you might think).4 Many talented artists, for example, are self-taught. But in order to create the work that so captivates us, they must achieve—on their own—a level of skill and craftsmanship that takes years or decades to master. This level of skill is also present in someone who handles, ships, and installs art in museums and galleries. Arts work is work, and arts workers are workers, something that the general population misses, I think, because it all looks so shiny from the outside. If they only knew how many conversations I have every month with arts workers who face financial instability, housing insecurity, and uncertainty about the way forward.

As far as claims of the arts being unnecessary, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis tells us that the creative industries generate $763.6 billion in economic activity, accounting for 4.2% of the GDP. And according to the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies, “The arts yield $27.5 billion in revenue to federal, state, county and municipal governments” in addition to generating a trade surplus of more than $20 billion, which ultimately provides a net gain for government. Why, then, would they think that offering more funding for the arts is a losing proposition? If the arts are that much of a boon to the economy with precious little support, consider what would happen if arts workers and art institutions were given adequate resources.

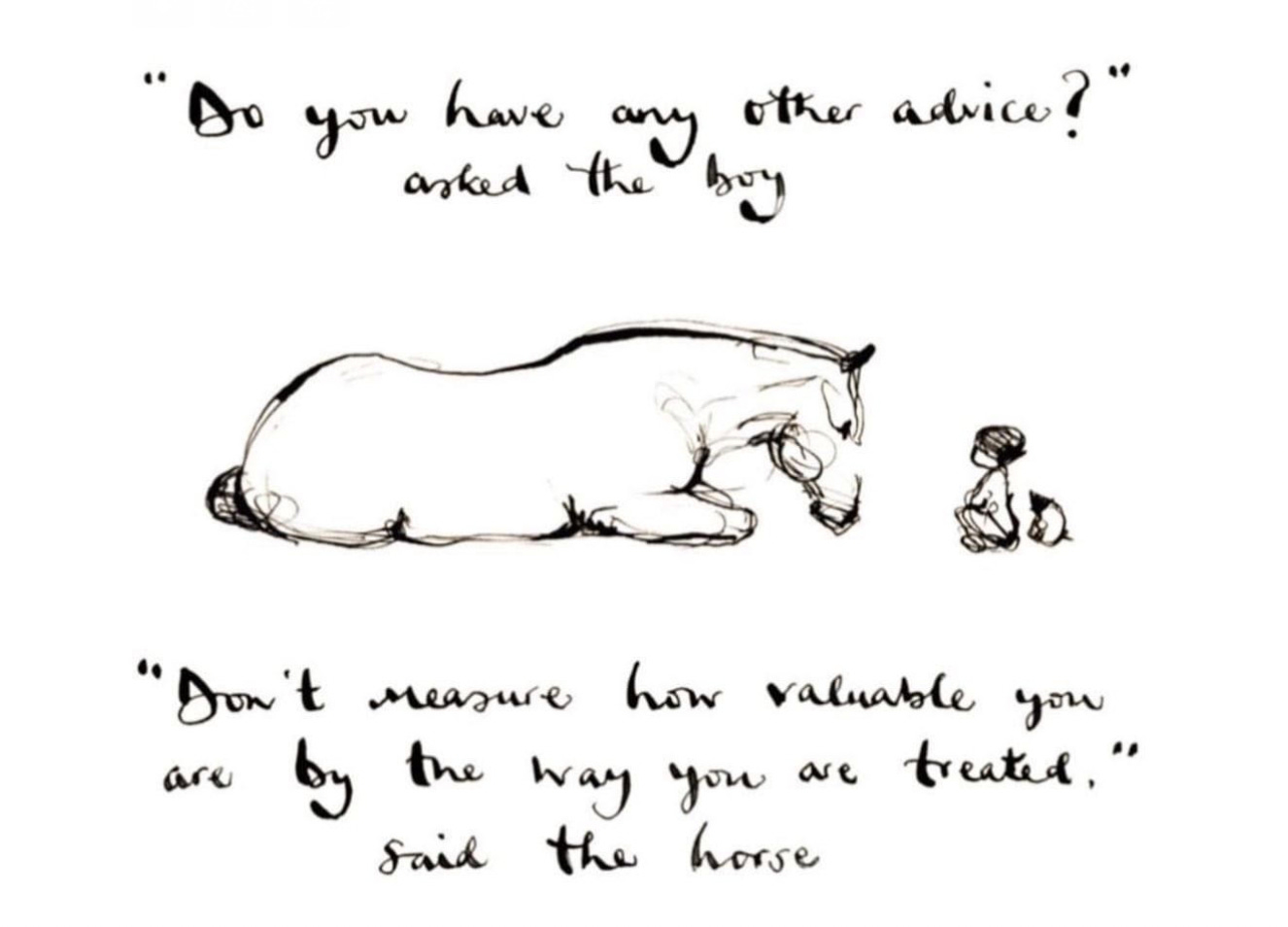

Of course, none of what I’ve mentioned—education, money, skill sets—represent the true value of art or arts workers. These are simply the mechanisms that people in positions of power use to measure things, which has very little to do with art itself.

The real value of art is that it opens up windows into the human experience. It challenges the power structure and allows us to look differently at the world. It makes us feel. It reminds us of our brief and exquisite stay here, in all of its turbulent beauty.

Arts workers know this. They recognize the full value of what art brings, both to us as individuals and to our society. It’s why they are willing to devote themselves to the professional roller coaster of opportunity and rejection, hope and fury, meaning and despair.

But they deserve more. And better. As teachers and librarians and plenty of other people know well, it’s difficult to live in a society where what you do isn’t valued. Arts workers are being failed by the very institutions—government, museums, nonprofits, galleries, etc—that benefit from their labor and their gifts.

That’s why, in addition to asking for more from these institutions, OUT OF THE BOX exists to encourage all of us to directly support living artists by collecting their work. This not only helps with the financial instability but with the feelings of rejection and despair. It is a way of letting an artist know that what they’re doing is making our stay here better.

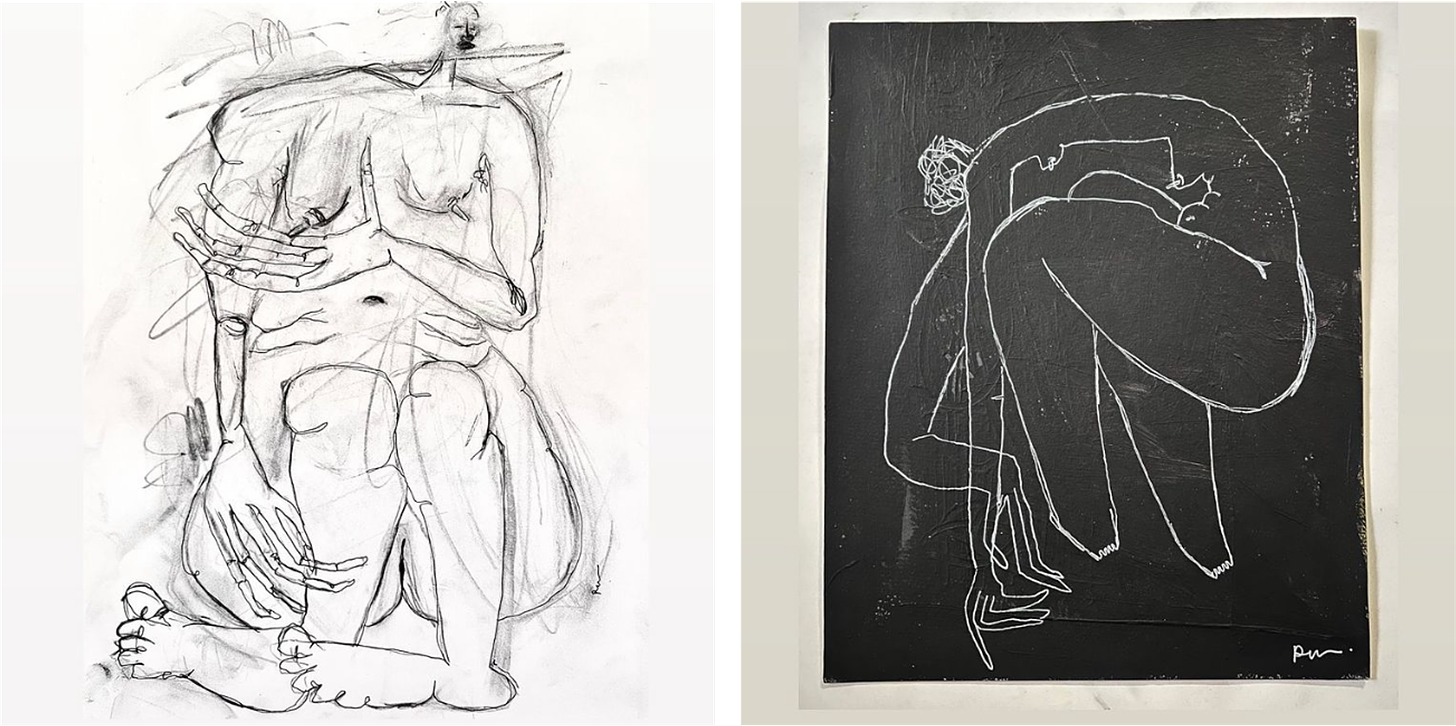

On the topic of supporting living artists, and in case you missed it on Instagram, Reneesha McCoy is having a studio sale that’s still going on, with her works on paper going for $50–$75. You can find her here or here and ask her which works she still has available. Whenever I hear about studio sales, I try to post information about them to my Instagram stories, so if you’re interested in collecting on a budget, follow me over there. Pieces sometimes go fast.

Recently, a reader suggested that I offer regular follow-ups on past articles and the people featured in them, which I thought was a lovely idea. This week’s update is a happy one:

A’Driane Nieves, the self-taught abstract painter whom I wrote about in the profile titled Paintings to Heal Our Broken Places, just announced that she’s heading to Europe for the summer where she’ll be having exhibitions of her large-scale paintings and smaller works on paper! It’s so nice to be able to celebrate the achievement of artists and members of the OOTB community.

If you want to keep up with A’Driane, you can sign up for her newsletter, which she mails out occasionally (so it won’t inundate your inbox) and includes personal and professional updates. You can also read her beautiful meditations about her practice on Substack.

I mean “the U.S.” when I say “we,” of course. Not you and me specifically. You and I are very much not a part of “we” in this case.

I’m trying to hold back a scream. Can you tell?

And in the case of Black and Indigenous arts workers, in particular, a soul-crushing amount of racism, microaggressions, erasure, and denied opportunities within the establishment.

A white supremacist system prizes pedigree and proof of accomplishment as determined by its own standards instead of taking each individual’s gifts into account.

Stunning piece! Deeply felt. When worlds collide and a nation comes under unprovoked military attack, who steps up first to lend a hand to the innocent victims? Two examples come to mind: Jose Andres' World Central Kitchen (millions of meals served in Ukraine –– and I consider chefs artists). And last weekend, the dozens of performers (artists) who played a benefit at Carnegie Hall. True, artists struggle. But they are often the first to step up to relieve others' human suffering. Call it moral rewards. Guess which team I ally with?

thank you for another poignant article, Jennifer. this is a lived experience felt deeply and personally in my bones. I just got Covid and have lost a week worth of work shifts (so far) at my "joe job". read as: service industry work. I have worked there for almost six years and hold a management position, and still, I don't have the honor or promotion or respect or laws on my side, for receiving sick time or sick pay, even in the midst of a pandemic. and so, I take a loss, a double hit. and things are going to be extra tight for the next few months. but I WILL keep making.*

*further note: I am fortunate to exist in a privileged enough place TO keep making. how many marginalized groups and individuals have not had such a luxury? how many have seen their best gifts and talents and passions sidelined because of an unexpected illness and too many sick days, rent increase, car break down, caring for family, inflation....insert other common every day problem here ______. these common every day problems fall hard on artists, creatives, and makers for all the reasons you described above. thank you for voicing them again.