[Community care: this piece contains mentions of death, familial estrangement, and suicide.]

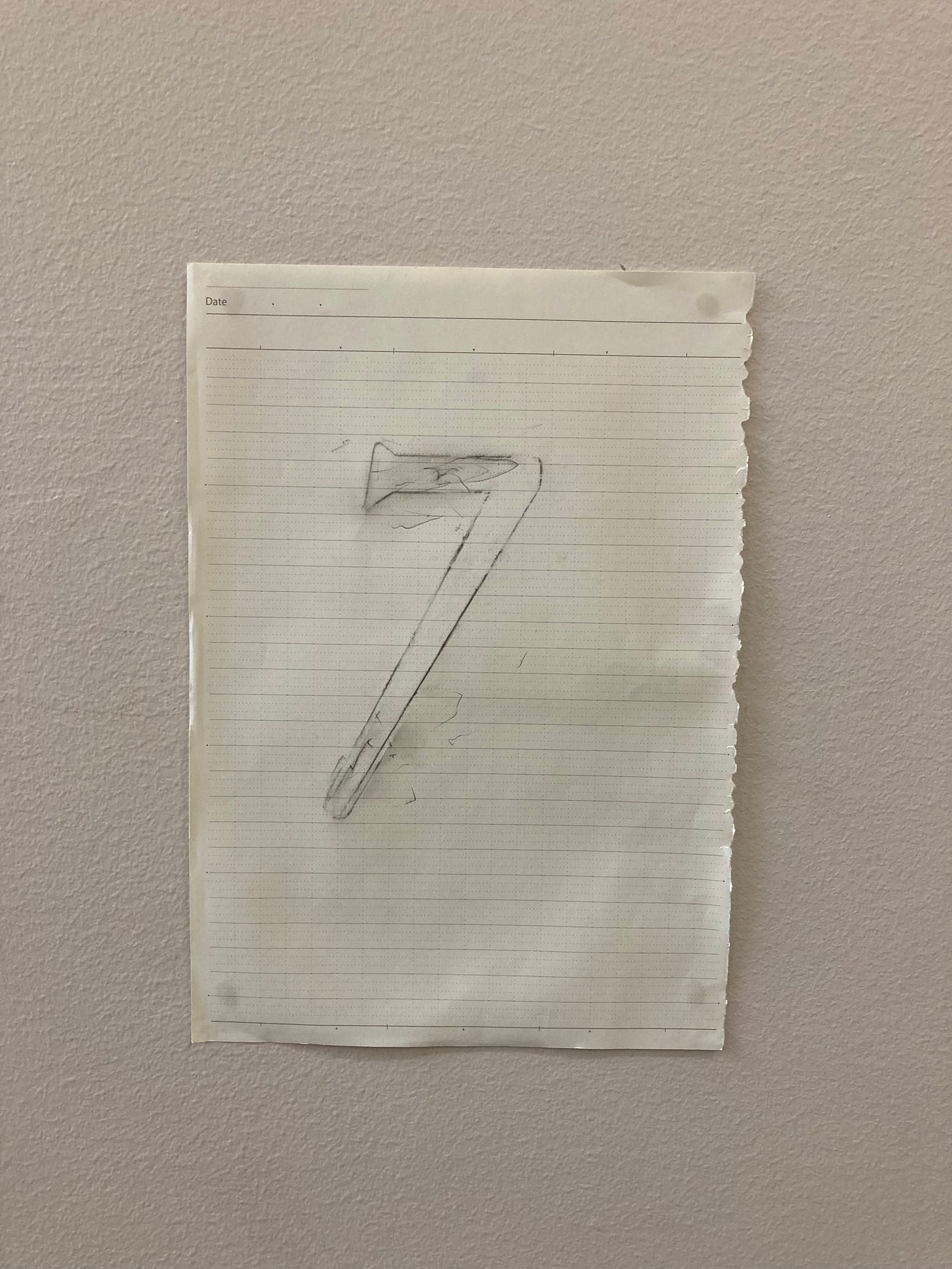

In the hallway outside the door to after/time hangs what appears to be a pencil sketch of the number seven on a piece of paper, jagged on one side from where it was ripped out of the artist's datebook. It turns out that it isn't a sketch, though. It's a rubbing that the artist, Jenn Sova, made of her father's apartment number in the way that people take rubbings from memorials or gravestones.

Sova made this piece, as well as the other pieces for her solo show DADDY, after she received a phone call last November informing her that her father—from whom she'd been estranged her whole life—had committed suicide. She was his next of kin, summoned to an apartment in nowhere Wisconsin to collect his things and to piece together the life of a man she never knew.

Apartment number seven was in a low-rent, high turnover building in a seedy part of town above a run-down hair salon, next to a Popeyes, a CVS, and a gas station.

This is where he lived.

Sova's learned that her father spent a lot of time at the pharmacy because the people who worked there were nice to him. Every day, at the same time, he walked to the gas station to purchase a cup of coffee and a pack of cigarettes.

A long, floor-standing light table at the back of the gallery calls to the viewer like a beacon through the dimly lit space. Atop its jarringly bright surface—in a piece titled Portrait of us—Sova has arranged a collection of ephemera that she took from apartment number seven, as well as material evidence of her connection to her father, which includes a vile of her saliva containing their shared DNA, and a photograph of him holding her as a newborn in the hospital wearing blue scrubs and a surgical mask. Along with these objects are the following items: a plastic case containing his dentures, two of his cigarette butts, and a small pile of his cremated remains inside the flimsy plastic sleeve from a pack of cigarettes.

These were his teeth. These were the cigarettes he smoked. This used to be his body.

The piece also includes a Ziploc bag filled with the artist’s partner’s hair, a way for Sova, who is queer, to expand the word “daddy” to include "the queerness of the term, to acknowledge the care and the chosen love and connections that we can control," she says.

Kneeling in front of the light table, I began to cry as I spoke to Sova's friend and fellow artist, Elizabeth Arzani, who was gallery sitting that day. "It's just so sad," I repeated while trying to ask questions through tears about the exhibition. She reassured me that she had broken down multiple times at the show and that it'd had that effect on many people. "This is a place for crying," she said.

I didn't tell her that earlier that day, before visiting the gallery, I was in bed drinking, trying to numb the pain from my recent estrangement from my own father, which has been too enormous and too devastating to contain or to process. I didn't tell her that the only way I'd convinced myself to visit to the gallery was to make myself a promise that if I did I could crawl back into bed as soon as I got home. But being in the presence of Sova's work and of Arzani's gentle understanding was helping me to release something that I hadn't been able to do on my own.

Along with the other objects on the light table lies a single latex glove, like the one Sova had to wear while sorting through the effects in her father's apartment.

The police kept trying to prepare her for what she would see when she arrived. He died in a chair, they said, and wasn't found for a week and a half. They told her about the smell, suggesting she bring a change of clothes. In advance of her arrival, she was consumed by the idea of the stain on the chair that he must have left behind.

When speaking to the local police about her upcoming trip to the apartment she told them, 'I'm coming to see it as it is. Please don't touch anything. I want to see how he lived.' She explained to these men—who were treating her as a long-lost beloved daughter in need of protection—that in addition to being his next of kin, she was also an adult and an artist. She didn't want anything changed from how it was. "It was nauseating to be in contact with them for weeks and to navigate their projections of the situation," she told me.

When she arrived at the apartment, all the furniture was pushed against one wall and the chair in which he died had been removed, along with the stain that had consumed her thoughts.

This is a part that's missing.

In order to recreate that absence, and to give her brain and imagination something productive to focus on, Sova created Remnants #1-98. The piece occupies an entire wall of the space, consisting of 98 works on paper, each with a different stain made from materials in Sova's daily life. The pieces are arranged in a 7 x 14 grid pattern, with seven (and its multiples) referencing the number of the place her father lived and died. Sova adds, "The number seven has such a history of being both lucky and unlucky—sacred and cursed—that kept coming up while I was making this work and going through the process of all this over the past months."

Another way that Sova works with absence to powerful effect is in the piece Next of Kin, but instead of conjuring a detail that wasn’t there, as she does in Remnants, she instead removes those that are. She presents this work as a thick stack of papers on the gallery floor, inviting visitors to take a sheet. Parts of her story are printed on each one with other parts erased. She first wrote the entire thing from beginning to end and then redacted it in 35 different ways (referencing the number of years she’s been alive to tell the story), creating an elliptical experience that mimics, I imagine, the sensation of not being able to put all the pieces of your own life together.

I'm so glad I saw the show on its last day instead of on its first, because time changes even the most carefully orchestrated things, whether they are works of art or events in our lives. The piece that first greets you when you walk through the gallery door—which began as a mirror covered in Vaseline save for where Sova had masked off the word DADDY—has undergone a significant transformation over the past few weeks.

This is how the piece looked when it was installed at the beginning of the month.

This is how it looked like when I visited.

Normally, I wouldn't share documentation that included me in it, but I'm not the only one reflected in this mirror. We all are. In the painful and inevitable slide of our fathers' mortality, or in their failure to meet our expectations, or in their vanishing from our lives. Everyone can see themselves in this changing surface.

As I drove home that afternoon, my GPS took me via a different route than I had come, down a thoroughfare that shares a name with my dad. I wondered how much of the trip it would tell me to stay on it, and when I would be signaled to turn off.

When I got home, I didn't get back into bed as I’d promised myself I could. I sat up and wrote about this show. I called Sova to ask her the questions that were circling my brain. Later, my best friend came over. They kissed my face and told me how much they loved me. I told them about the exhibition. We celebrated chosen family and the weight that Sova had helped lift from my heart in the gallery that day.

These are the ways that we exorcise ghosts, how we create rituals for ourselves to drive out the things that haunt us and to call in the healing we need. Art does not exist in sterile white spaces. Artists make it so that we can take it with us.

so timely that i have a catch in my throat. thank you!

Thanks for this beautiful write-up of your experience, and your generosity in being vulnerable regarding your own, unique context when viewing the show. I didn't go see it—part of me wishes I had, but the louder part of me was pretty sure I wasn't in the right space for work like this. Looking at documentation photos and reading your words help me experience it from a slight remove—a more intellectual place. I don't think that's generally the best way to experience art, but sometimes it's the only way. And it's wonderful to know that though the exhibition is ephemeral, its ghost will live on in documentation.