Life is Beautiful

Or it will be if Joey Veltkamp has anything to say about it.

On a searingly hot afternoon in late July, I spoke to artist Joey Veltkamp via Zoom. Me, from Portland, Oregon, and Veltkamp from the home in Bremerton, Washington that he shares with his husband, artist Ben Gannon, and five pandemically acquired cats. (Long story short: one turned into two. Two turned into a litter.)

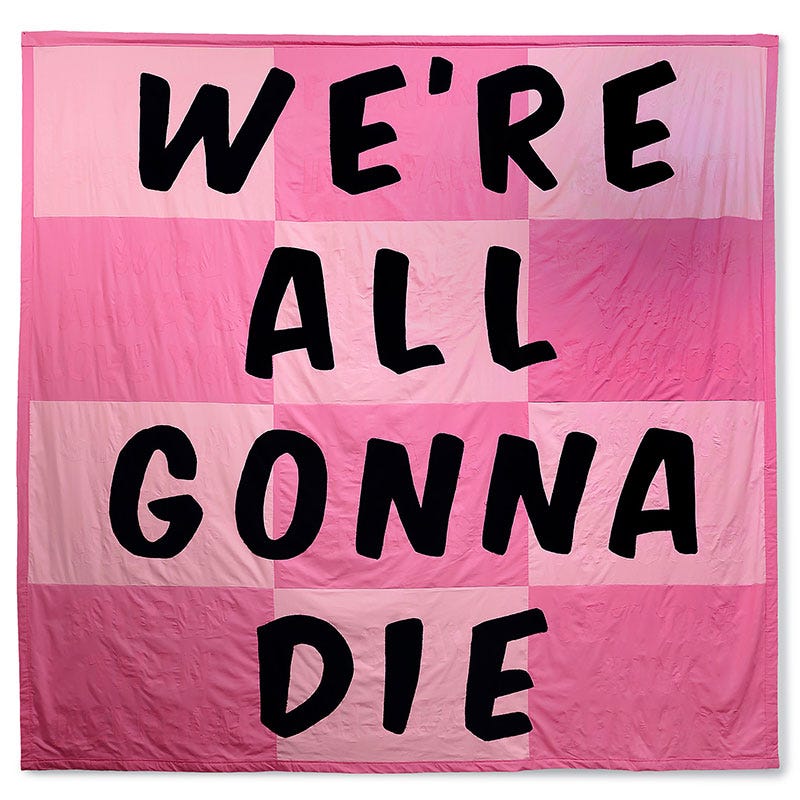

I knew that I wanted to talk to Veltkamp, whose solo exhibition is currently on view at the Bellevue Arts Museum, the first time one of his textile pieces come across my Instagram feed. It was a bright pink quilt with large black lettering that said WE’RE ALL GONNA DIE. It struck me as a witty and fatalistic carpe diem urging us to make the most of whatever time we have on this giant rock spinning in outer space. Not everyone felt the same, he assures me. When he told his mom about the piece, he recalls her getting angry. “She was immediately like, ‘Why do you do this shit? Why don't you do something nice to this world and say something like Life is beautiful?’”

He titled the piece Life is Beautiful.

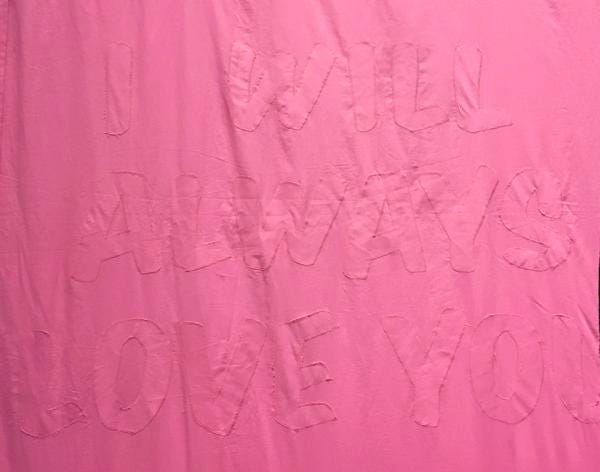

If you get close enough, you’ll see the contradiction sewn onto its surface. In the same pink fabric Veltkamp used to make the background, he stitched the lyrics of the songs he listened to in the studio to keep depression at bay. Among them, “Sun in Your Heart” (from the theme of Life & Times of Grizzly Adams), “La Vie En Rose” (Grace Jones), “I Feel Better” (Hot Chip), and “I Will Always Love You” (Dolly Parton).

Veltkamp is careful not to refer to his fabric pieces as quilts, using the term “soft paintings” instead. "I feel like the quilting tradition is so specific,” he says. “I think if you tell the local quilting bee that there's a beautiful quilting show at the museum, they're going to be disappointed when they go. But if you tell them there's this weird show that kind of dabbles in quilting, they're going to have their expectations set a little bit.” It seems important to him, as a self-taught artist, to respect the lineage of craft and to avoid co-opting a tradition that he doesn’t feel a part of.

It’s clear from the way that Veltkamp approaches his work, though, that each piece is imbued with everything that makes a quilt a quilt: the desire to comfort and to be useful and to spread love from the maker to the recipient. He speaks of them as functional objects, not as works of fine art: when I ask him what the dimensions are for the largest piece in the show he replies, “A large queen-size. No, there's probably one that's a king.”

Before the opening of the exhibition, a registrar from the museum contacted him to inventory all the pieces that Veltkamp had sent over. The museum was concerned because some had arrived stained. Veltkamp quickly reassured the person on the other end of the line, "I was like, 'Oh, those are all intentional.’” Because he wants to make objects that are lived in, he builds “brokedown-ness” into them, often using fabrics that already have stains on them. “I hate this preciousness,” he says, “this idea that like ‘Oh my god, I got a grease stain on this [shirt], I can't wear it anymore!” Veltkamp gives garments a second chance to be loved.

He laments the fact that since he got gallery representation and the price points of his work have gone up, so too has the level of preciousness surrounding it. Even the folks who bought pieces years ago, before any of them were hanging in museums, have told Veltkamp that they’ve started taking them off of their beds. This feels sad to me. If the artist’s intention is for an object to be used, it should become more valuable with wear.

When I ask him how he sources fabric—trying to get a sense of how he makes materials choices and which fabrics he uses to convey meaning—he wants to talk about the ethics of fabric and how fast fashion is killing the planet. According to the National Resources Defense Council, “Textile mills generate one-fifth of the world's industrial water pollution and use 20,000 chemicals,” many of which are carcinogenic. The industry poses an existential threat to planetary health, which Veltkamp takes very, very seriously.

Years ago, he procured cheap denim from the local thrift store, happy to be recycling fabrics and keeping his footprint as small as possible. But then he had a realization that went something like this: “Great, you're getting two dollar denim, you're cutting it up to make a quilt that you're gonna sell for three thousand dollars, and this unhoused person would have worn those [garments] for a job or something.” He says it’s impossible to make an ethical decision and that the most ideal solution is using his and Gannon’s clothes. “I will literally go up to the closet sometimes and be like ‘I need yellow. This shirt's coming downstairs now.’”

Veltkamp’s work is strange and quixotic, nostalgic at times, and most of his pieces are irrepressibly cheery. As a result, the darker pieces that he made as a response to and as representations of Trump’s America—the country pick up truck with a tattered flag flying in back, and the burning American flag against a blue backdrop—feel even darker by comparison.

Veltkamp had been preparing for this museum show for the past three years, during which time he and Gannon settled into comfortable, quasi-hermetic domesticity together. “Ben and I, we realized during the quarantine that we're the kind of couple that probably could have gone to Mars and been fine," he says. At one point during our conversation, a delicious looking beverage appears in Veltkamp’s hands, as though by magic. “Oh, it's affogato time! Thank you!” Veltkamp exclaims, looking up at Gannon who remains just out of frame.

Veltkamp is quick to mention that the only reason he’s been able to devote himself to working on the show full-time is because Gannon has a steady job with amazing benefits.

We both agree that artists need to have this conversation more often, and in public, because there is a false perception in the art world and beyond that successful artists are self sustaining. In fact, those artists are the exception. He tells me that when he and Gannon first moved to Bremerton—an hour’s ferry ride across the Puget Sound from Seattle—their finances were tight. He took a job making chocolate chip cookies in Seattle to help supplement their income. “So many people tried to shame me about it, like, ‘I thought you were doing okay, I thought you were making it.’ I guess we have different definitions of making it. I’m happy to contribute to our household,’” he said at the time. “Certain people have looked down on me both because the job was beneath me and just because I had to take a job.” He adds, “I remember early on some galleries saying ‘You can't have a job and show here.’ That's just as weird. Even if we didn't financially need it, which we did.”

Despite having become something of a darling in the contemporary art world, Veltkamp doesn’t consider himself a contemporary artist. He seems to actively resist the trappings of the fine art world, using the term “queer folk artist” to describe himself. Perhaps it’s because he didn’t appreciate the box that being “a successful artist” put him in, or maybe the view is simply better from the outside: working in his basement studio, hunched over his crappy sewing machine in his non ergonomic chair, wearing a stained shirt, a few paces from his husband who is busy in his own studio, surrounded by their accidental herd of cats.

Love his work! It’s not just that you deliver us to artists that make an impression; you have a way of introducing us to them that feels like we’ve sat and had a wonderful and rich conversation. Illuminating, human, and never superficial. As varied as the artists themselves and the art they make. Also this line: “If an artist’s intention is for an object to be used, it should become more valuable with where.” A thousand times yes.

Didn't think I could love Joey Veltkamp more but your writing made it so