The Importance of the In Between

In the art world, artists are either having an exhibition, working toward an exhibition, or they cease to exist. Within a capitalist framework, we think of exhibitions as jobs, so when an artist doesn’t have one, they are—like unemployed people—considered to be “between things.” Exhibitions represent the positive space in an artist’s life and everything else makes up the negative abyss. We have taught artists that they hold no value for us during these between times, that they are not even worth talking to, which is wildly unfair—not just to them but to us as well.

It’s my experience that the in between times are often more important (not to mention more interesting) to an artist’s development than the periods when they are actively making something for our consumption. It’s during these fallow periods that they frequently gain a fuller understanding of what they’ve made, why they made it, and how it fits within the context of their lives. And if you’re lucky enough to talk to them during one of those periods, you get a fuller understanding of those things, too. This week I had the pleasure of interviewing Nigerian-American transdisciplinary artist and educator, Bukola Koiki, who gave me a whole new appreciation for the in between.

I first saw Koiki’s work in 2016 at an exhibition called Foreigners,1 which featured the work of four artists who immigrated to the U.S. Two pieces from that show have stayed with me through the intervening years, and one of them is the Nigerian gele (head tie) that Koiki made from Tyvek. When I saw it, the Tyvek brought to mind images of the gimcrack subdivisions that pop up from sea to shining sea: the quintessentially American blight of new construction. I wondered if the artist was marrying a traditional garment from her mother country with the insatiable desire for newness of her adopted country.

When I asked Koiki about it, I learned that her reasons for choosing the material were both simpler and more complicated than I had imagined. The practical reason is that Tyvek is the closest analog to the synthetic material that Nigerian women use to wrap their heads. Like Tyvek, a common gele2 fabric is stiff and paperlike to allow it to hold its shape. It creases permanently, which means that even when it’s refolded or restyled, it carries the memory of the previous times it was worn.

The ways of tying the gele, like the fabric itself, can be passed down from mother to daughter. When Koiki, who left Nigeria to attend undergraduate and graduate school in the U.S., traveled back home to attend her sister’s wedding, she was struck by what she had missed. “I don't know why, but this was the panic that I had: Damn it, I will have to tie a head tie and I don't know how to do that. It's something I would have learned had I stayed home going to events with my mother. I would’ve learned either by osmosis or my mother teaching me how.” When she came back to the U.S, that experience informed her practice. She said, “I wanted to make work about what it means to try and claim [the rite of passage].” She titled the series I Claim That Which Was Never Mine.

Koiki is incredibly thoughtful and intentional with her materials choices. Every element in every piece is there for a reason, so I was not surprised to learn that the Tyvek serves another conceptual purpose. “It’s this protective thing for homes, which referenced the conversation I was having in the work about the meanings of home if you haven't been there in a long time,” says Koiki.

So much of her life and practice seems to be about making sense of these liminal spaces. Twice during our conversation, she paraphrased a bell hooks quote about the elusiveness of home and how it ends up being not just one place but many different locations. Koiki stitched the quote onto a very recent piece,3 which she credits with pulling her out of a long fallow period.

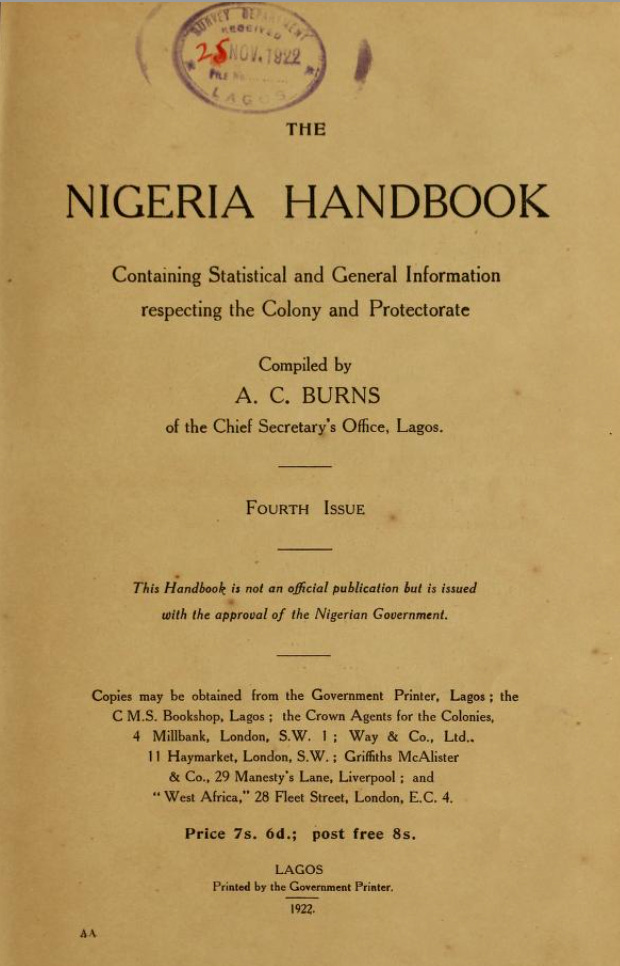

She tends to deal with these fallow periods—and with the oppressiveness of Covid—by researching her way through them. “I think the thing that, frankly, saved a lot of my own mental space is being a nerd. Anything I’m interested in, I will research it into the ground.” One of the things that has captured her attention for years is The Nigeria Handbook, which she originally discovered in 2016 in the Smithsonian library digital archives. The first edition was printed in 1917—over a decade after colonization—with a new edition being released every year for decades. The 1921-22 edition, which Koiki read in the archives, was written by a British colonial officer who later went on to be the governor of one of the colonies in West Africa.

“As I looked through this book, I was appalled,” Koiki remembers. “Suffice it to say, the book itself was a catalog of Nigeria's resources and a travelogue for the European trader who would come to extract the resources of this country to increase their wealth. It might as well have served as an annual report, since I learned that they actually did have an annual report—the way companies do—for every colony in the Africas.” Later editions, she says, contained ads for haberdashers, clothing makers, hat makers, soap makers, and “of course makers of other sanitary things because, you know, it's the black planet and very, very, scary and you must disinfect everything for dear life. It was just everything to the comfort and the ability for the white man to walk freely through the African jungles and hopefully make it home in one piece with more money and more resources.” One of the ads she found was for Barclay’s Colonial Bank.4

This was in 2016, mind you, when Nigeria was on Trump’s list of shithole countries. “I was so pissed, as we all were, and bereft and horrified,” says Koiki. “And whatever semblance of a dream I thought it was like living in America, I’m sure I never imagined this guy who is so similar to the tyrants I’d read about only in history books.” She wanted to make work about The Nigeria Handbook and couldn’t help but draw parallels between the way that the British colonists wrote about the African people and what she referred to as “the ever-present language of pestilence that [the Trump administration] used to talk about immigrants and immigration.”

While thinking about materials, Koiki found netting bags that protect people and crops from pests. Using cotton thread—a material with connections to the Black body—she hand-stitched the bag into a newly modified ad for Barclay’s Bank. After making the physical object, she sealed it, inked it, and printed the image onto cotton paper with an etching press. This, I learned from Koiki, is called a collagraph.5

After the printing process, the original object is intact but forever transformed, having taken on a patina and a certain threadbare quality. As a romantic, I can’t help but find it even more beautiful than the original, but I will leave it to your tastes to decide for yourselves.

Originally, Koiki planned to show only the collagraph, but decided to exhibit the physical object along with it. And because it contains the memory of the original object, when it’s shown alongside the collagraph all three states of the work’s existence—the physical object before printing, the collagraph, and the physical object after printing—are present at once.

This makes me think about the ways we narrowly conceptualize our states of being. The positive and negative space of an artist’s career. The before and after. The important parts and the in between parts. If I could only take one thing away from my conversation with Koiki—an artist who isn’t entirely at home in her adopted country or in her country of origin—it would be a more fluid understanding of place and states of being.

What if home isn’t a single place, like bell hooks says? What if we can stitch ourselves and our sense of home together, as Koiki does every time she makes work? What if all we have is where we are and what we choose to make of it?

Pronounced GAY-LAY

I don’t have a picture of it to show you because that’s how it works in the between times. But it gives us something to look forward to.

I shit you not, that’s what it was named.

Excuse me for taking the lord’s name in vain, but I swear to god that I learn about a different printmaking technique at least once a month and they never seem to run out because there are a kajillion of them and they are all extremely complicated and singular and difficult to understand for anyone like me who has no experience with printmaking. Thanks to Bukola for her endless patience in having to explain this to me eighteen different ways before I understood what the hell was going on.