[Community care: this post contains adult themes, adult language, and a mention of rape.]

I have watched the documentary 69: The Saga of Danny Hernandez, about the rise and fall of rapper Tekashi 6ix9ine, more than a dozen times. Not because I find it enjoyable, but because it’s a near-perfect case study of how the attention economy works.

A young Hernandez—who was raised by a single mother and whose beloved stepfather was murdered when Hernandez was a teenager—decided at an early age that he was going to lift himself out of poverty and achieve worldwide fame by whatever means possible. Best way to do that? Grab as many eyes and wag as many tongues as possible.

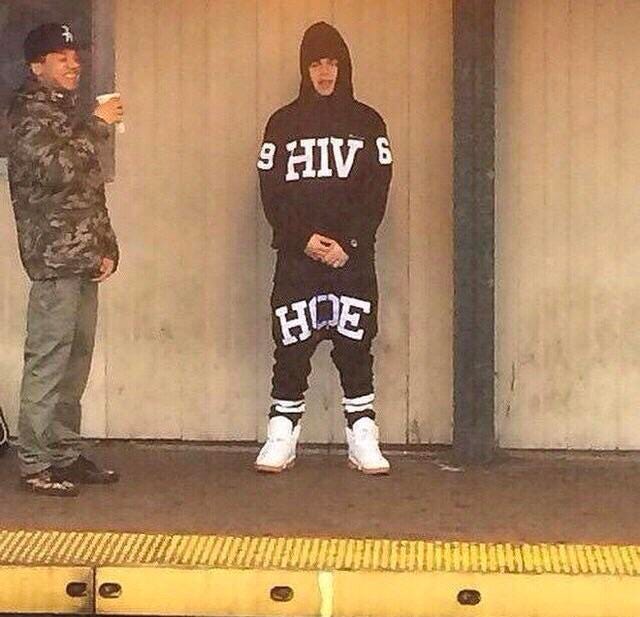

Knowing intuitively that any attention is good attention on the road to celebrity, Hernandez started touring the neighborhood in a custom-printed wardrobe designed solely to draw gasps and stares and requests for photos from strangers.

Hernandez started making music with other Brooklyn rappers, coattailing off of their already-established reputations. He appropriated his stage name, Tekashi 69, from a friend’s roommate, the Japanese tattoo artist Takashi Matsuba.

The video for Tekashi’s first single “69” opens on him getting a blowjob from a faceless woman, the camera then following him through the streets of Brooklyn as he dangles out of Lamborghini windows while spouting some of the laziest most misogynistic lyrics you can possibly imagine. But no one really cared about, or even paid attention to, the lyrics. All they saw were the shiny things: the sex, the cars, the lifestyle.

One of his collaborators, Shadow the Great, who shot Tekashi’s next video describes the experience like this: “I went to his house. They just had a whole bunch of props and shit, like a whole bunch of keys of cocaine props bagged up and I’m just like, ‘Yo, what the fuck am I shooting right now?’ I was all for it. Like, at least he’s not killing people…He’s trying to create this crazy shock-value content so people can look at it and be like ‘Oh, what the fuck is this?’”

Tekashi harbored no illusions or aspirations about the quality of his music. Former friend and collaborator, Seqo Billy, says in the documentary, "I got a call, and my manager was like, 'Yo, you wanna meet this kid?' I pull up, [Tekashi] played his stuff. I liked the videos. And that's how he was presented to us, through videos. He told us hisself his music was trash: 'My music is trash, my video fire.’"

The filmmaker followed up, asking Seqo, "What did you think…when you heard that?"

"I thought it was genius," he replied.

To make himself even more of a spectacle, Tekashi died his hair rainbow unicorn (before that was a thing) and started sporting a rainbow grill. The podcaster Adam22, who gave Tekashi his first interview before he was well-known, posted a photo of Tekashi to announce their upcoming chat. As Adam recalls it in the documentary, it blew up Tekashi’s Instagram in a matter of twenty-four hours: “I hadn’t even put the interview out yet. But just from a photo, just from people looking at him, he got 10,000 followers in a day. I just remember that really standing out to me.”

The numbers kept climbing as Tekashi’s videos became more and more sensational. He seemed unstoppable. Even after doing jail time at Rikers for raping a thirteen-year-old girl—which, notably, did not put much of a dent in his following—and being barred from making sexually explicit videos, Tekashi just leaned harder into images of gang violence, drugs, crime, and excess.

The kids, as they say, loved it.

Why am I spending time researching and writing about this? Because this is the content that visual artists working today have to compete with. Visual culture is like a book that someone has highlighted every line of: when everything is designed to jump out at you, nothing jumps out at you anymore. It’s just a neon scream. Artists are forced to constantly up the ante1 to get our attention,an audience full of junkies who need stronger visual smack to get us high.

Images have to grab us by the throat to get us to stop scrolling for two seconds. And even then, it’s on to the next shiny thing.

But what about artists who make pensive work, work that takes a minute to settle into, to figure out, or to roll around in your mind? What about artists whose work is subtle, layered, or—god forbid—nuanced? When I think about the work that has most affected me, it often takes some effort and time to understand. What are those artists meant to do in a world where fast attention is money, in which careers are dictated by the almighty algorithm? These are the existential questions that keep me up at night, and maybe they keep you up too.

So I’m wondering if there’s something we can do about it together:

Today I’m announcing a new addition to OUT OF THE BOX: the subscriber-only chat!

It’s a conversation space in the Substack app that I set up exclusively for my subscribers (paid and unpaid), that functions like a group chat, live hangout, or private social network for folks who love art.

One of the ways I’m so excited to use this feature is to create a place where artists can post their work (in progress or finished) without having to worry about grabbing the attention of the algorithm, and where other artists, art lovers, curators, art historians, and collectors who are part of this community can see what they’re up to. Together we can create a space that is deeper, more thoughtful, more nuanced, and more open to discussion than social media. Let’s circumvent the attention economy. Let’s say F*CK YOU to the algorithm. Let’s embrace things that might be slower or quieter or require a bit more pondering.

There will be other types of chats as we go, but this feels like a nice place to start. I’ll also post thoughts, questions, and updates along the way, and you can jump into the discussion any time. What’s great about the chat, which is different from comment threads, is that everyone can post pictures!

The details

To join our chat, you’ll need to download the Substack app. Notifications about new chats are sent via the app, not through email like the newsletter is. Turn on push notifications so you don’t miss a chance to join a conversation as it happens. (If you want to avoid notifications, you can always check the app to see if there are any new chats to join.)

How to get started

Download the app by clicking this link or the button below. Chat is only on iOS for now, but chat is coming to the Android app and desktop soon.

Open the app and tap the Chat icon. It looks like two bubbles in the bottom bar, and you’ll see a row for my chat inside.

That’s it! Jump into our thread to say hi, and if you have any issues, check out Substack’s FAQ. The interface is incredibly simple and intuitive!

I’ve already started our first chat thread so come on over and say hello!

Not even Tekashi is immune. He must always go bigger, shinier, more spectacular. The saddest thing I discovered, while poring over at least 10 hours of additional interview footage of the rapper (and more Instagram videos than I care to admit), was the below clip of Tekashi explaining where the 69 moniker comes from. The reason it’s sad is because it’s the most thoughtful thing I’ve heard come out of his mouth and he never talks about it. The interviewer, Angie Martinez, had to pull it out of him:

Drop a heart or a comment below to support the conversation and the community.

Such a worthy illumination. Technology changes have brought widespread access (in theory) but have just shifted the nature of the fight for artists of quieter work. The struggle to be seen, shifting from a lack of adequate outlets and platforms to a plethora of platforms all so crowded by noise that they occlude everything, on-and-offline. In TV and film, I often notice quieter, more subtle/nuanced work getting attention, an antidote to the constant bombardment of louder forms. It seems a far, far steeper climb among the visual arts community given the algorithms they’re up against.

I hope I can figure out this Substack app. I'm not shy, but I am a bit of a Luddite.