Scrolling through Twitter last week—in a misguided attempt to find solace and camaraderie amidst the ongoing horror—a long thread popped up on my feed from an account I'd never seen before. The account is run by someone claiming to be an educator and arbiter of culture. Each tweet in the thread contained two side-by-side examples of everyday objects—offices, doorbells, doorknobs, bathrooms, bridges—that pervade our lives and which we often take for granted.

Each image on the left was an example, according to this person, of something beautiful and all the images on the right were examples of something ugly. He was not presenting this as his opinion, mind you, which I would've welcomed with great enthusiasm for debate. This was his taste, preference, and unacknowledged bias for Eurocentric aesthetics masquerading as fact. He was declaring—to his one hundred thousand pliant followers—what was objectively good and objectively bad. I think I burst a blood vessel in my brain reading through the thread and the comments.

It's essential to a healthy culture that we seek out voices that encourage our curiosity and exploration, that aim to illustrate something's value simply by loving it in front of us. That effort will either change our opinion or it won't. Either way, no harm or judgment has come to anyone. And even if we don't grow to love that thing or even to appreciate it, we will likely never see it exactly the same way again. Isn't that what we're all doing here: enriching and expanding each other's experience of the world?

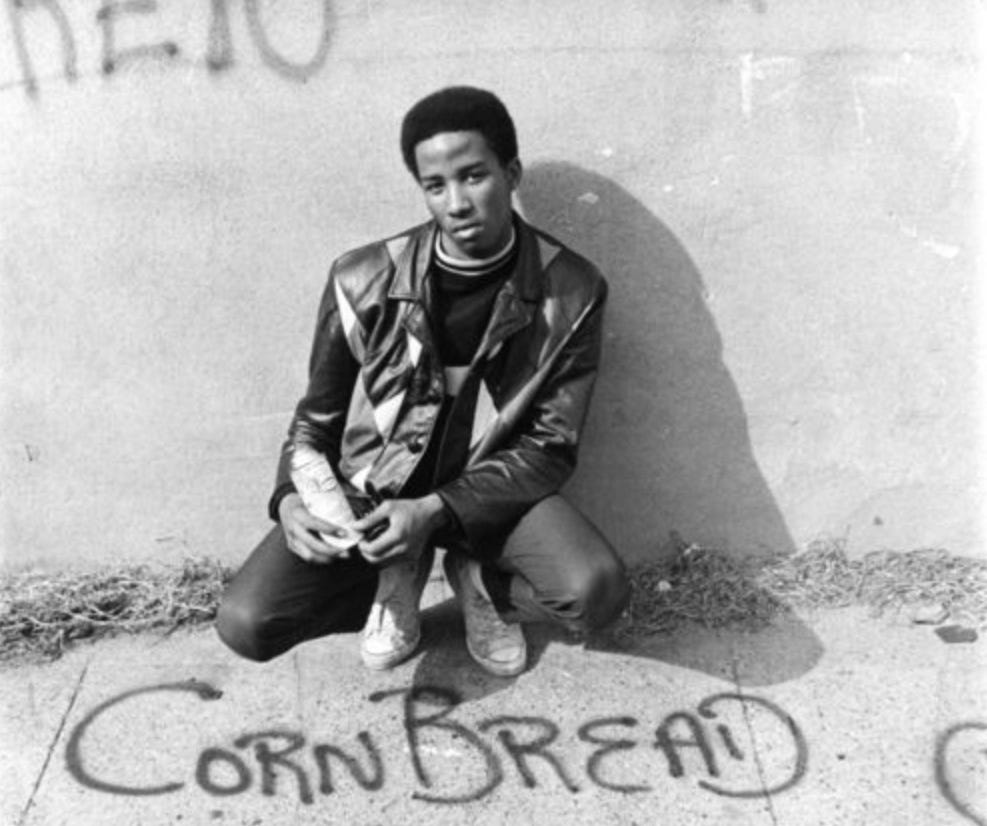

One of the things I love most—and I'm saying this without a speck of hyperbole—is graffiti, which is something that many people hate with an abiding passion. This thing I love, this thing that gives me more joy and delight and pleasure that almost anything else, is considered by most a blight.

I should clarify: when I say graffiti, I'm not talking about officially-sanctioned murals or what has come to be known as street art (though I sometimes love those things). I'm talking about a gleaming train car so completely transformed by a crew of bombers on the overnight shift that in the morning none of the original surface of the train is visible. I'm talking about the colorful throw ups exploding new life onto forgotten walls that are otherwise crumbling into nothing. But most of all—oh, most of all!—I love the shitty illegible tags that litter the grimy underpasses of every city.

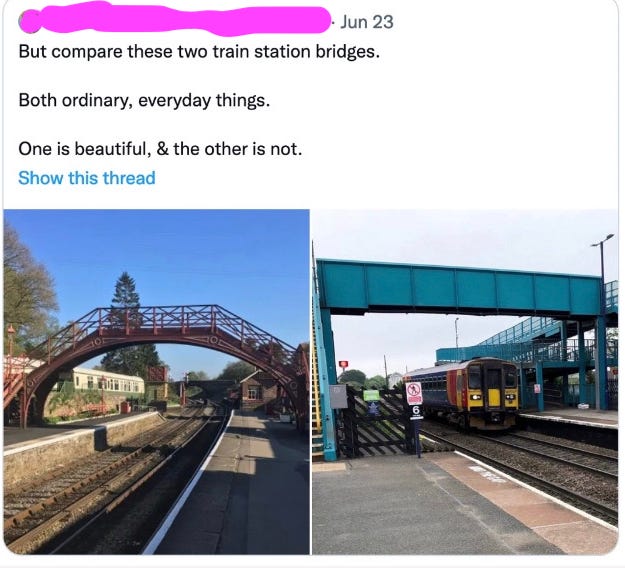

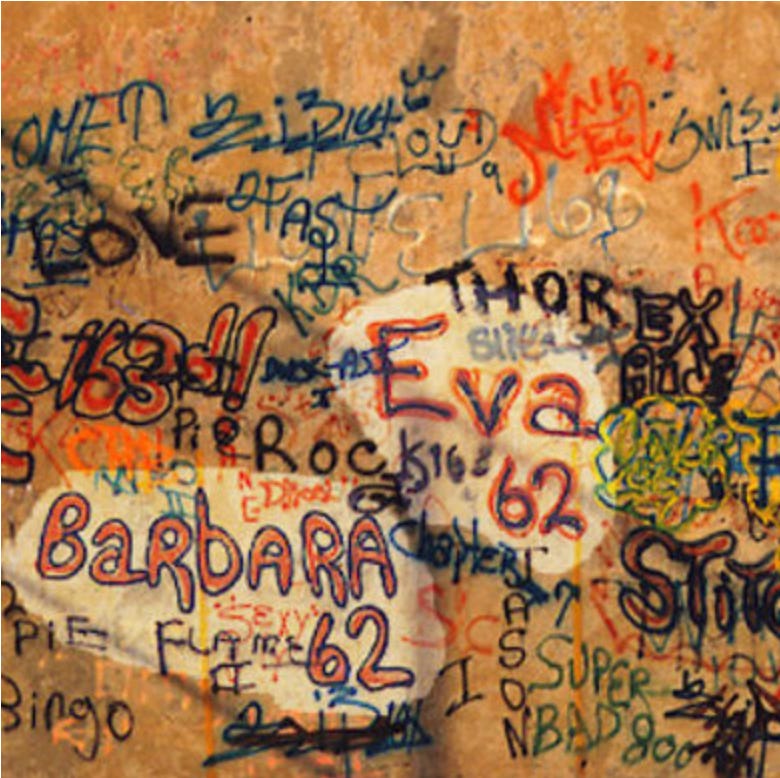

Graffiti in the U.S. came into mainstream awareness in the 60s. Two of the earliest and most well-known graffiti writers of the time—there is some dispute about who was first, depending upon whom you ask—were Cornbread (a.k.a. Darryl McCray) in Philly and TAKI 183 in NYC.

What they had in common was that they used their nicknames, like so many graffiti writers who followed them, as their tags. McCray got the name Cornbread as a young kid in juvenile detention. He said, "Everybody talked about my name all over the jail. So I figured that if they're talking about my name all over the jail, they will talk about my name all over the street. And that's exactly what happened. The more they talked, the more I wrote."

The 183 in TAKI's tag was a reference to his address: 183rd Street in Washington Heights.1 He worked as a messenger—traveling far and wide throughout the boroughs for his job—bringing his tag along with him. That sparked the practice of other bombers using their name and street number in their tags. This was a way for kids who were ignored and underestimated by society to be known and to be seen. This is who I am. This is where I come from.

So when I find tags scrawled on train tracks, utility boxes, telephone poles, the backs of stop signs, and the sides of abandoned buildings, I don’t see destruction or vandalism.2 To me, every mark screams I WAS HERE. I MATTER. I see the person behind the mark. I see their desire to be acknowledged, to be counted among the precious.

Graffiti challenges the notion of what is beautiful. It also shines a light on who gets to be angry in our culture as well as who and what are considered threats. When I briefly explored the neighborhood app Nextdoor, I encountered lots of privileged white home owners complaining about graffiti (that was nowhere near where they lived) as though it was the root cause of our city's problems and that eradicating it would solve everything. Nothing a fresh coat of paint can't cover. The same thing that gives me overwhelming pleasure as I walk or drive through our shared spaces is that which upsets other people's sense of order.

So while a Twitter account that self-assuredly compares two doorbells or two bridges to one another may seem like a harmless trifle, it is a microcosm of a larger and more powerful impulse that we're currently fighting against. It represents an effort to impose and control standards of what is pleasing and displeasing, what is good and bad, and what is acceptable and unacceptable. This is the same mechanism that decides who gets to be angry, who gets to claim injury, who gets the right to exist without fear, and who is afforded sovereignty over their bodies and their land.

These are not small concerns. They cut to the heart of how we build an equitable society. In Goethe's 1811 autobiography, From My Life: Poetry and Truth, he wrote "I was, after the fashion of humanity, in love with my name, and, as young educated people commonly do, I wrote it everywhere." We have to reckon with the reality that the systems which have long encouraged an educated white man’s desire to put his name on everything have intentionally criminalized the same behavior when anyone else dares to take up space.

He admits to cribbing the idea from JULIO 204, who was the first in NYC to use his address but whose graffiti writing career was short-lived.

To be clear, nothing I have said should be taken as condoning the tagging of private property, houses of worship, or nature spaces.

I appreciate and mostly agree with your idealistic vision. But it also comes from privilege. You have clearly never lived in the ghetto. You have never found your car scribed all over. Or your garage tagged up. Unfortunately lots of tagging and graffiti does occupy private, spiritual and natural space. Yes it may be saying: "Here I am, acknowledge me!" But it also often stands for "turf" or "tribe" marking, perpetuating violence, toxic masculinity, disrespect of property, personal achievement and just about everything and anything that can be disrespected for the sake of bad ass-ness or one upping your peers, etc. It is another complex layer of society that can be viewed in many different ways.

That bridge photo popped up in my twitter feed last week and I spent a while looking at it trying to figure out which was supposed to be the 'non beautiful' one and then I had flashbacks to White Dudes™ in art school and kept on scrolling. Kudos to you for writing through it.

Also, I love that someone loves the illegible underpass tags.