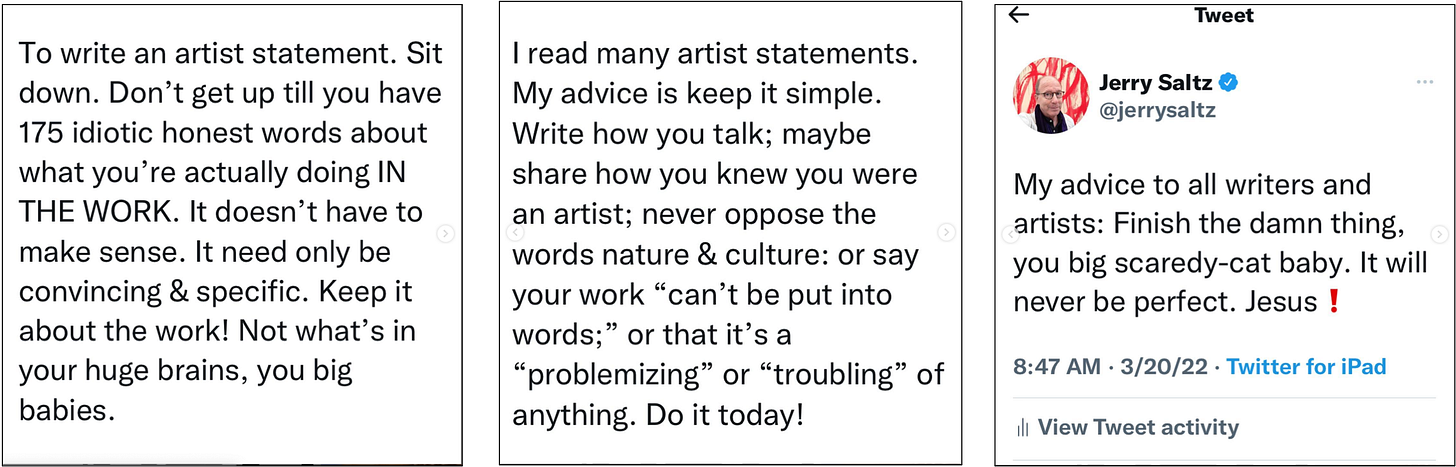

As sometimes happens, I had a different post scheduled for this week, but something came to my attention that begged to be written about. Jerry Saltz, the Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic for New York magazine whom I respect and with whom I agree 90% of the time, posted something on social media about artist statements that compelled a rebuttal:

He goes on:

First, a short primer for non-artists and new collectors1 about artist statements:

An artist statement—whether it appears on the wall of a gallery or on an artist’s website—is a finicky and mercurial requirement that is often a source of great consternation for artists, and rightly so. Imagine someone asking you to distill your life’s purpose and philosophy in under 300 words, and you’ll have some sense of the task. It’s nearly impossible. And yet, artists are asked to do it all the time. Part of the difficulty is that an “artist statement” means different things in different contexts. Sometimes, it’s a generalized description of an artist’s practice that follows them from show to show and doesn’t change. Other times, an artist is called on to make a statement for each body of work. Both of those things are referred to as “artist statements” even though the latter is actually a “work statement.” But that’s a topic for another time.

I agree wholeheartedly with certain things that Saltz says, namely: don’t waste your words telling us that your practice can’t be put into words. But, to me, the fact that he has to specify this is indicative of a much larger issue, which is that the overwhelming majority of artists are visual thinkers and have a difficult time translating the experiences that they’re having in the studio—and the motivations that brings them there—into written language.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve interviewed artists over the years who’ve said to me, “Talking to you is helping me understand what this body of work is about.” Sometimes it requires a conversation to be able to metabolize and externalize all of the thoughts and feelings you’ve had alone in the studio for months. It’s not always as simple as sitting at your keyboard and pounding out 175 words when someone (who can easily do that in their sleep) tells you to.

For the artists who struggle with writing about your work, consider asking a trusted friend if you can talk to them about what you’re working on and if they would be so kind as to take notes on the points that stand out to them (non-artists: consider volunteering yourselves in this capacity to the artists in your life. I guarantee it will be a glorious conversation). This will help capture your voice and to crystallize the main themes of your work. And because you’re talking to someone who knows and loves you, your creative and vulnerable self will come forward more than if you try to sit down and write a disembodied statement that you think strangers will want to read.

Another strategy is to picture a member of your community—preferably a young person or an elder—who doesn’t know anything about art but is curious about what you do. If you knew you could have their undivided attention for three minutes, what would you want to say to help them appreciate your work?

Furthermore, the function of an artist statement is not, as Saltz says, to describe your work “so a blind person would have an idea of it.”2 Anyone can do that. An artist statement should be something that can only come from you, an intimate window into your practice, your brain, or your soul.

I’ve read hundreds (thousands?) of artist statements over the years, and in preparing to write this piece, I wanted to share one with you that has stood out and stayed with me during that time. It was written by Ervin A. Johnson for his 2017 exhibition titled #InHonor:

I began #InHonor as a personal response to the killings of Black people across America. To be completely honest the work was born out of guilt. All of my friends had rallied up in arms to march for Trayvon Martin and Eric Garner. I, on the other hand, was nowhere to be found. I felt guilty. I consider myself, for the most part, a conscious individual and so my silence became a burden. When the time came for me to be vocal with my peers I chose the path of cowardice. What real change would come of my presence as a young gay black man at a march in which half of my people don’t accept or acknowledge me? Still, though, I felt moved to do something. Whether or not I was accepted was something I had and will always deal with. I had to come to terms with that before anything else.

#InHonor is a series of photo-based mixed media portraits made to honor Blackness as it exists in its various forms. More specifically it speaks to the violence and destruction occurring across America, in the form of police brutality. The skin color is removed from each portrait and then aggressively renegotiated. Pigment stands in for an idea or preconceived notion about a particular type of human experience. That experience is culminated and summed up in a word: Black. Questions of tangibility and digital approximations of an entire race are raised. What does a digital approximation of skin color mean and what does it mean to physically remove it and reapply it? The faces are forever transformed, just as our world is with each loss of life.

As you can see, there’s some description of the work itself, but the statement functions as a generous, human, fallible container for it. We feel like we know the artist, that he trusts us, that he has invited us to see under the hood. It’s not formal or stilted or full of big fancy art words. It’s honest and raw and straightforward.

Please don’t misunderstand: I’m not saying that artists are required to open a vein for our benefit. Quite the contrary, sometimes a body of work is purely aesthetic or comes from a place of unadulterated delight. If that’s the case, say that. We will revel in your delight along with you. Work doesn’t have to come from pain. It just has to come from you.

Similarly, let your artist statement be something that only you could write at the moment in time that you write it. It doesn’t have to speak for you forever. But if it’s simple and honest, it will speak to us for a very long time.

We have a No Art Lover Left Behind policy here at OUT OF THE BOX. No elitism allowed in the clubhouse and no one is ever assumed to have a certain level of art knowledge. So, if you ever have a question about something, or if I’ve failed to make something clear (which, forgive me in advance, is inevitable), please ask in the comments! No question about art is ever too small or too big or will ever be disparaged. If you’re wondering about something, you can be sure that lots of other folks have the same question.

Mind you, this is an entirely different conversation about the importance of accessibility and accommodation. Every artist and every art space needs to be able to provide descriptions of the work for anyone who needs or wants them, but that is not the same thing as an artist statement.

Thank you, Jennifer, for these thoughtful comments on the practice of artist statements. Many artists think they must sound profound which is an unfair burden. My favorite is probably by Jasper Johns who got right to the point, although he was being directive and not introspective: “Take an object. Do something with it. Do something else with it.”

That pretty much describes what I do with my work. My statement reads:

“I think with my hands. I don't tell them what to do and they don't tell me why they did it. That's the only way we get along. Each mark I make is a little window into a rented room where a collective of unreal shapes, lines, and colors jostle for position. Some stay, most get up and leave. Wrong party. Over days and weeks, if I am lucky, a confident figure starts to move, laugh, think. One day, it turns to me and says, ‘Hey, you there, you in the filthy apron, pour me a Scotch.’ As it’s not polite to let a painting drink alone, I pour two.”

David Slader

Dslader46@gmail.com

Davidslader.com

I've read this several times. Really helpful. I've found myself tripping over explaining my work sometimes as I try to parrot my own artist statement which doesn't feel right. That's why I like the statement that you shared—it's vulnerable, deep, authentic and unpretentious. You've motivated me to rework mine (which I don't think I've ever said). Thanks!