I should start with a confession: I’ve often struggled with minimalist art.1 I appreciate it, but it rarely stirs anything inside of me that makes me want to cry, sit down, or reevaluate my life. In my experience, it tends to either require a formal analysis (Look at the way that line intersects with that other line!) or it functions like a wire hanger over which we as viewers are meant to drape our own interpretations and projections (It’s a powerful statement on the commercialization and commodification of religious practices! No, it’s a comment about the urgency of global warming!). Franky, it feels like a lot of work for little pleasure.

I mention this only as context for how surprising it is that I continue to be drawn—like a cosplayer to Comic-Con—to the site-specific installations of minimalist artist Avantika Bawa. If you, too, are someone who finds minimalist art to be a bit of a head scratcher, bear with me. We’re going somewhere great.

I first encountered one of Bawa’s installations when I walked into the darkened ballroom of the crumbling Astor Hotel2 where she had erected a towering golden scaffold, dramatically uplit to cast a web of broken shadows on the walls and ceiling of that once-resplendent space (more on this later).

Scaffolds are central to all of her installations, but unlike other minimalist sculptures that insist we contemplate their geometry or mathematical ratios or use of positive vs negative space,3 Bawa’s scaffolds are not intended to be the sole focus of her work. In addition to the beauty of their rectilinear cadence, they’re also trying to get you to look at other things.

Bawa uses prefabricated aluminum scaffolding4—in all its functional, ubiquitous, unremarkable glory—as a shorthand for building and construction. These interchangeable metal pieces become the language she uses to talk to us about the built environment, the influence humans have over our surroundings, and our relationship to place.

In the case of the Astor Hotel, the glittering scaffold was there to draw our attention to a faded empire, the pitfalls of dynastic wealth, and to show us what the floor of the club looks like once the lights get turned on.

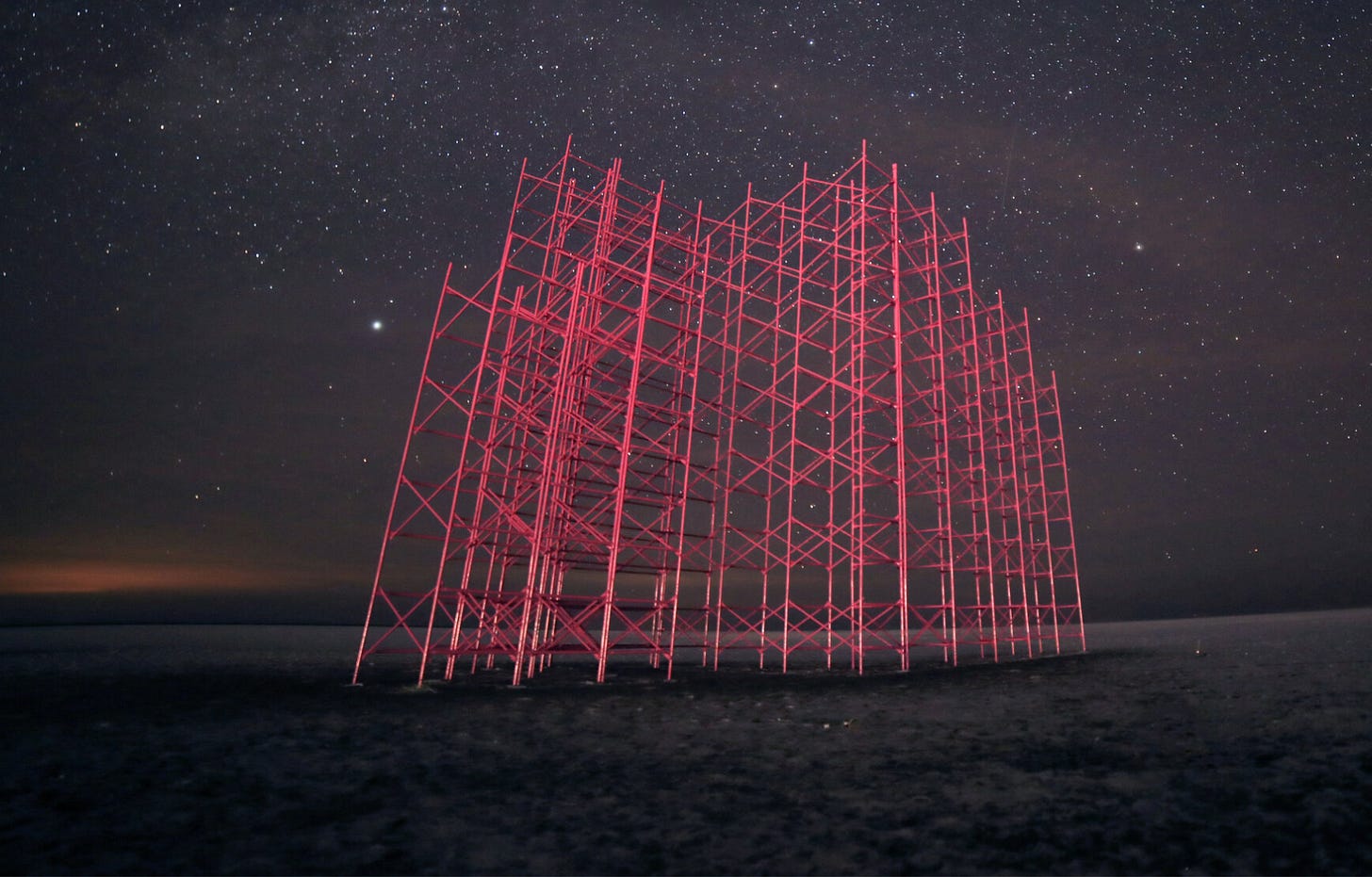

When I found out about one of Bawa’s newest installations, my heart skipped. In the winter of 2019, Bawa traveled back to her native India to install a 40-ft-tall pink scaffold on the Rann of Kutch, a 2900-square-mile salt flat on the border between India and Pakistan.

The area remained desolate and depressed until decades ago when the patriarch of a now-prominent family returned to his village in the Kutch after having studied abroad, and decided he wanted to revitalize the economy. “He figured that by extracting bromine5 from the salt, you could create a factory. So the economic landscape of that region changed because this man decided he wanted to save his own village instead of continuing on in the West,” says Bawa.

At the same time, his spouse decided to take it upon herself to save the dying art of embroidery in the region.6 “Because it's such a nomadic space, there are lots of little tribes, and each tribe has its own distinct embroidery style that was being lost,” Bawa tells me. With the help of this family, handicrafts and the economy quickly prospered. “Fast forward thirty, forty years,” Bawa laughs, “I come in and say, ‘Can I put in this chunk of metal?’”

Bawa selected a location that was a two-hour drive from the nearest city, turning the destination into a de facto pilgrimage. In addition, “the site itself is surrounded by all these glamorous things called ‘tent cities’ where people flock in December to explore and hang out in the Rann,” Bawa said about the agglomeration of mini hotels and motels that attract tourists from all over the country.

Fortuitously, on the night of the scaffold’s unveiling, the main tourist attraction on the flats became too muddy to visit. Having nowhere else to take their customers, the guides rerouted their camel tours to investigate the new pink glow that they’d spied off in the distance.

When I asked Bawa why she’d chosen pink as the color for the scaffold, she sent me three photos:

So, you see, the scaffold isn’t just about the scaffold at all.

It’s about the beauty and resilience of the region. It asks us to consider the people who contributed to its prosperity, as well as those who traveled miles to be there—by car or camel—to congregate and celebrate across a vast and inhospitable landscape. It pays tribute to each pair of hands that erected and painted every inch of it, so that the pilgrims would have something to gather around.

But that’s only the first part. In February, the scaffold was taken down and re-installed—in an entirely different configuration—close to the bromine factory so that the workers would be able to appreciate it for a month. In March, Covid swept through the region, making it unsafe for the crew to de-install the scaffold. So they simply left it up.

Then the monsoons came and took the scaffold down.

Instead of mourning the destruction of the work, Bawa considers it a different piece altogether, made in even closer collaboration with the region. She retitled it A Pink Scaffold: The Collapse. Like its predecessor, it begs us to reflect on its surroundings, which, in the time of Covid, now extend to all of us, everywhere.

For me, this is the piece of art that most symbolizes the pandemic: the steadfastness and surety with which it once stood and the unpredictability of the forces that turned it upside down. The reason it’s so beautiful in its collapse, I think, is because, like us, it has resilience and resurrection in its bones.

WEEKLY DISCUSSION THREADS

I heard you guys loud and clear about wanting weekly discussion threads! The first one will be this Friday at 10-11am PT (1-2pm ET). I’ll remind you on Instagram the day before, and we can shift the time window in subsequent weeks if we find one that works better. Or we can have open discussion threads that don’t require a set appointment. We’ll figure out what works best as we go. In the meantime, I’ll meet you here on Friday at 10 am PT.

Named after John Jacob Astor, the U.S.’s first multi-millionaire, who made much of his fortune smuggling opium into China. He helped create the world’s first opioid epidemic, which continues today thanks to the Sackler Family. If you want to learn more about them (and their heavy ties to the art world), I highly recommend watching Dopesick (Hulu) and The Crime of the Century (HBO). Make sure to have on hand: Kleenex and a pillow to scream into.

In speaking with Avantika, we both realized that we didn’t know the difference between “scaffold” and “scaffolding.” We discovered that “scaffolding” is the term for the materials/modular parts that make up a “scaffold.” She gets her scaffolding from Home Depot.

Bromine is used in agricultural chemicals, insecticides, dyes, pharmaceuticals, flame-retardants, furniture foam, gasoline, plastic casings for electronics, and film photography.

The end piece "The Collapse" and your tying it into the pandemic is what connected me most. The collapsed remains of a strong, solid presence in the world is exactly how I feel, as well as the question as to whether it can ever be rebuilt.

As someone who often feels like a head-scratcher-in-the-face-of-minimalism, I’m so glad to have seen this work! It’s mesmerizing and I have no problem understanding why you (and so many others) are drawn to it. It’s moving, in some ways that I understand quite clearly and in others that are nebulous but no less meaningful for being so. I especially love that you shared the background of the location. It adds layers of context that make me wish I’d been there in person. Also, this line will stick with me: “The reason it’s so beautiful in its collapse, I think, is because, like us, it has resilience and resurrection in its bones.”