Rip-off or Homage?

The answer lies in how we determine what is essential to an artist's expression.

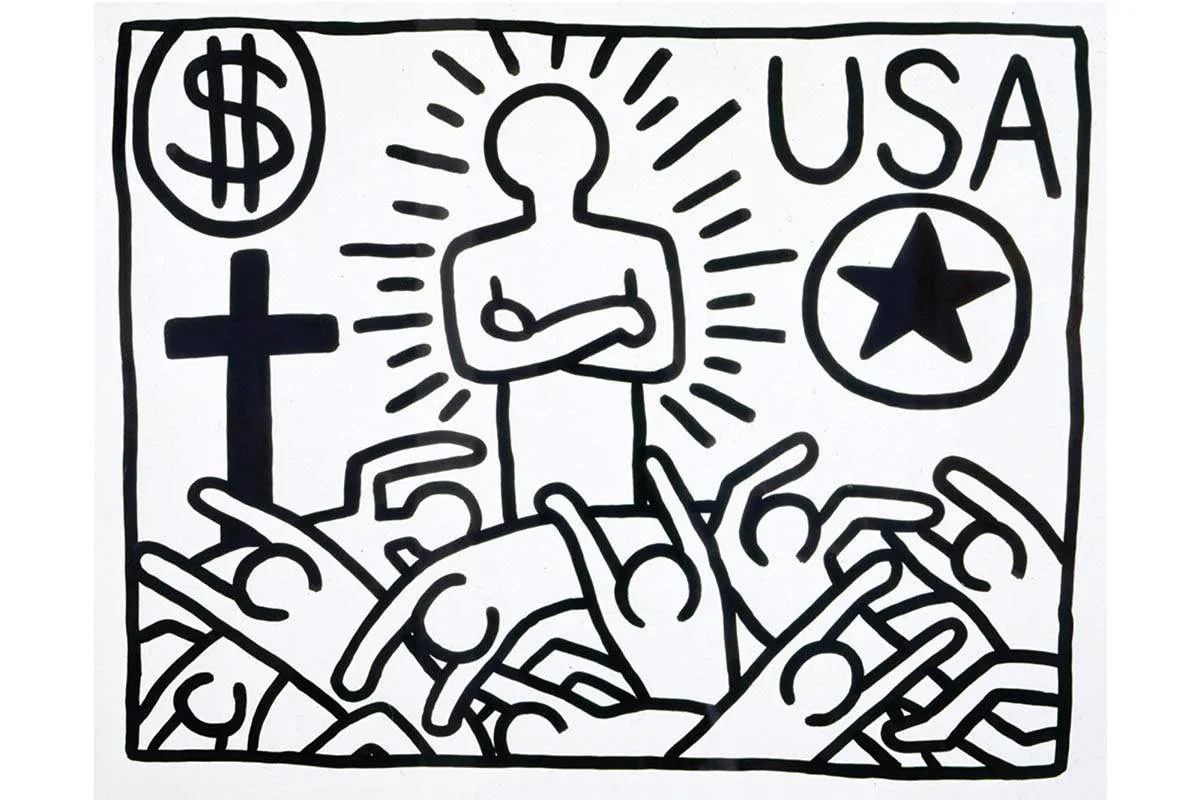

It’s my belief that the mark of a great artist is that the through line of their expression—we might also describe it as their voice, their aesthetic signature, or the essence of their practice—is so strong and so singular that once you become familiar with it, it is forever unmistakable. If you were to see one of their unattributed pieces out in the world that you’d never seen before, you’d immediately know it was theirs. I’m not talking about pieces that are so ubiquitous that anyone would recognize them (think: The Girl with the Pearl Earring on Linda-from-HR’s coffee mug). I’m talking, for example, about the line work of Keith Haring.

The style of portraiture of Ronald Jackson.

The otherworldliness of Wangechi Mutu’s figures.

The rendering of the female form of Raneesha McCoy

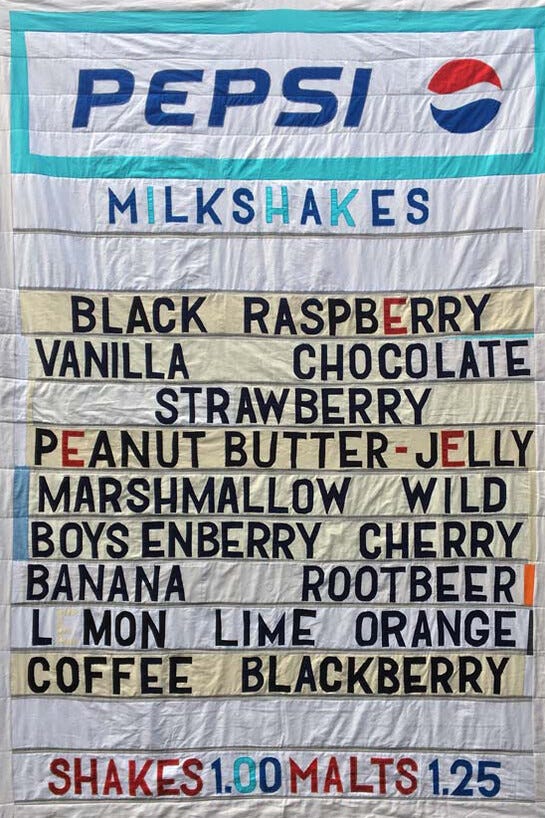

The sweet absurdism of Joey Veltkamp’s textiles

(You needn’t be familiar with all of these artists for the theory to hold. The point is: now that you’ve seen examples of their work, you’ll be able to identify the artists should you encounter other pieces in the wild.)

Deborah Roberts is one of these artists, which is to say an artist who has made a name for herself with an unmistakable aesthetic signature. Her collages juxtapose found photographs with hand painted details and incorporate black-and-white photography with color photography to comment on Black identity, oppressive beauty standards, Black joy, resilience, and the inequities of race in the U.S. Another hallmark of her work is the way that she distorts, exaggerates, or highlights different features of each of her figures to draw our attention to them and force us to ask questions about what we’re seeing.

The reason I’m thinking about the singularity of artists’ practices in general, and of Roberts’s practice specifically, is because this week she brought suit against another artist (and that artist’s gallery) for copyright infringement.

Roberts, an internationally recognized and well-established artist, claims that collages made by Lynthia Edwards, a younger up-and-coming artist, are so similar to her own as to be nearly indistinguishable, even to those who are familiar with Roberts’s work. She claims that Edwards’s replication of her aesthetic and technique is so complete that many people who see Edwards’s pieces believe them to be created by Roberts.

As you can see from the above images, all of the hallmarks of Roberts’s style—the subject matter, the mixture of color and black and white found photography, as well as the manipulation of certain features in each figure—are present in Edwards’s collages.

According to ARTNews, Edwards’s representative asserts that “both Roberts and Edwards draw from a long tradition of collage, which has a historical importance for Black artists.” He goes on to say, “Deborah Roberts does not own the photo collage tradition that she’s working in. She didn’t invent it. She has absolutely no legal rights to it. It was developed by a group of artists over the last century, that she was not a part of.”

Roberts counters with the fact that Edwards and her gallery were aware of and actively exploiting the fact that “the more the Edwards collages resembled the Roberts Collages, the more successful the Edwards collages became with purchasers.”

Both sides make reasonable arguments, and the details of the case are interesting for many reasons—not least of which is the fact that its outcome will establish important legal precedent about artists’ intellectual property and ownership. But, above all, I can’t stop wondering how we are meant to identify and quantify something that is in many ways ineffable and unquantifiable, something that is felt as much as it is seen.

After having spent a good deal of time looking at both artists’ work, I'm able to notice nuanced differences between the two: Roberts’s collages feel tighter and more minimal, and Edwards’s work often contains more visual noise.1 But I would put my ability to accurately distinguish between the two in a blind test at about 65%.

So we must ask ourselves: what constitutes the irreplicable and non-transferrable core of an artist’s work? How do we separate that which is fundamental to a particular artist’s expression—that which is uniquely theirs—from the ways that they influence artists who come after them?

Artists are constantly influenced by other artists.2 Would the current situation be different if Roberts and Edwards weren’t contemporaries and Edwards was simply paying homage to the legacy of an artist who had predeceased her? Would the calculus change if a more established artist had borrowed from a less established one? What are the factors worthy of consideration?

I’m not here to offer an opinion about whose claim has more merit. I’m interested in hearing artists’ and readers’ thoughts about where you think the line exists between copying another artists’ work and being influenced by that artist. How do we determine an artist’s creative fingerprint? How do we identify the unique signature of their soul as manifested through their practice?

I say that as a completely neutral statement, not as something that has positive or negative connotations.

If I had a nickel for every unoriginal but well-intentioned Basquiat rip-off I’ve seen in my life, I could retire tomorrow.

Such a vital question and an excellent breakdown of it. In my New York crowd of artist friends (visual art, theater, and film), this discussion usually fell into one of four categories: inspired by (where we feel that something new has been created), homage (seeming to clearly point toward the inspiration), derivative (works that felt like bland but not ill-intentioned copycatting without original thoughts), and outright copying (which felt most like a craven scam to make money). It always seemed easiest to manage this discussion when the artists were of different, or slightly different, generations. For artists coming up together, it can definitely get trickier and harder to sort. In the best cases, it seems like people can bounce off each other and everyone can bring new things to the table. In the worst, it feels like one is riding the other’s coattails because they can’t come up with their own directions. When one is established and the other is not, obviously it brings a dangerous power dynamic to bear. We certainly have seemingly endless examples of well-known artists stealing work from unknown artists and claiming it as their own, and their power status affords them the opportunity to do so, often without any repercussions. But there are also instances of lesser known artists quietly making a living by flying under the radar while copying well-known artists’ work. It’s a sticky wicket to sort it all out and feels inherently resistant to a standardized-rubric solution. In my own circles of working artists, so much of it comes down to intent and generally requires discussion to sort out.

Great conversation, Jennifer. Thank you for exploring it so thoughtfully. It's hard because sometimes artists do invent a technique. Generally, though, I think this question of plagiarism has to be evaluated not only through the lens of material and process (which the legal defense seemed to focus on) but also by considering subjective intent and viewer take-aways (which your article did). Can a signature be made the same way but have a different life to it, making it a different signature? It seems like that doesn't apply to this case. One other thought: How does profit change the evaluation process? If the artist wasn't making any money off of this work, would anyone care if it was copyright infringement?